2024. May 1. Wednesday

- Budapest

|

|

Address: 1065, Budapest Nagymező utca 8.

|

The exhibition has closed for visitors.

2015.10.13. - 2015.11.29.

Food is life. But what can we do if there is none, and when the prospects for its availability are bleak? Bergen-Belsen, Germany, was one of those concentration camps, which served as a destination for the deportation of several thousands of – mostly – Jewish people, and the scene of their captivity during World War II. We cannot know too much about the life, horrors and starvation the captives experienced there – only a few of them survived the hardships, and those who did, would not speak too much about this part of their lives. By now most of the survivors have passed away, so it remains to the following generations to process the truncated, traumatic past, which can be reconstructed merely from some fragmented memories.

Eszter Biró’s grandmother Vera was taken from Szeged to Budapest, then to Bergen-Belsen, when she was 16 years old. She only took two items with her that were especially important for her: an illustrated album titled Kétezer év festészete (2000 years of painting) edited by Sándor Bortnyik – Iván Hevesy – Márius Rabinovszky, which had to be left in the Budapest ghetto because of its size and weight; and a notebook in which she recorded a collection of her favorite poems with a pencil. In order to endure the horrors of the concentration camps, it was essential to recall memories and keep one’s religious-cultural traditions; therefore many tried to practice their religion – even if it meant risking their lives, – and collected prayers and stories. Some of the women tried to escape the starvation by returning to their memories of the times they spent in the kitchen and recalling recipes. Vera erased the poems from the notebook brought from home and replaced them with recipes. The soups, meat-dishes, marinades, fillings, garnishes, cakes, and biscuits became unreachable dreams, just like the ingredients: fresh water or a bag of flour.

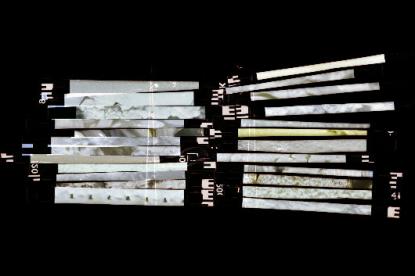

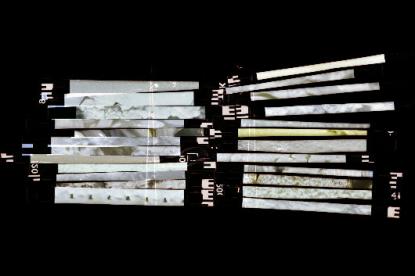

In many cases the recipes in the collection have imprecise measurements or missing ingredients, making them almost impossible to prepare, and often there are poem-fragments next to them from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and János Vajda. Eszter Biro – just as she did in several of her earlier works dealing with the use of archives – handled the recipe book as a kind of symbolic archive. She took photos of the ingredients on film, and then cut up the negatives into strips to compile them into abstract visual recipes based on the original pages of the recipe book. In the exhibition at the Project Room, besides the original recipe book and the pages processed by Eszter Biró, the cut-up negatives of the photos are also displayed in the exhibition space as a symbolic aspect of the unavailable food and ingredients.

The processing of the past in this case is remembering the remembrances. Keeping memories is nothing else than keeping traditions. The recalling of memories – that was once an agent of survival – is now a remedy for forgetting.

Judit Gellér

Eszter Biró’s grandmother Vera was taken from Szeged to Budapest, then to Bergen-Belsen, when she was 16 years old. She only took two items with her that were especially important for her: an illustrated album titled Kétezer év festészete (2000 years of painting) edited by Sándor Bortnyik – Iván Hevesy – Márius Rabinovszky, which had to be left in the Budapest ghetto because of its size and weight; and a notebook in which she recorded a collection of her favorite poems with a pencil. In order to endure the horrors of the concentration camps, it was essential to recall memories and keep one’s religious-cultural traditions; therefore many tried to practice their religion – even if it meant risking their lives, – and collected prayers and stories. Some of the women tried to escape the starvation by returning to their memories of the times they spent in the kitchen and recalling recipes. Vera erased the poems from the notebook brought from home and replaced them with recipes. The soups, meat-dishes, marinades, fillings, garnishes, cakes, and biscuits became unreachable dreams, just like the ingredients: fresh water or a bag of flour.

In many cases the recipes in the collection have imprecise measurements or missing ingredients, making them almost impossible to prepare, and often there are poem-fragments next to them from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and János Vajda. Eszter Biro – just as she did in several of her earlier works dealing with the use of archives – handled the recipe book as a kind of symbolic archive. She took photos of the ingredients on film, and then cut up the negatives into strips to compile them into abstract visual recipes based on the original pages of the recipe book. In the exhibition at the Project Room, besides the original recipe book and the pages processed by Eszter Biró, the cut-up negatives of the photos are also displayed in the exhibition space as a symbolic aspect of the unavailable food and ingredients.

The processing of the past in this case is remembering the remembrances. Keeping memories is nothing else than keeping traditions. The recalling of memories – that was once an agent of survival – is now a remedy for forgetting.

Judit Gellér