2024. April 26. Friday

Budapest Museum of Fine Arts - Budapest

|

Address: 1146, Budapest Dózsa György út 41.

Phone number: (1) 469-7100

E-mail: info@szepmuveszeti.hu

Opening hours: Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00

|

The exhibition has closed for visitors.

2008.06.03. - 2008.08.31.

Museum tickets, service costs:

|

Ticket for adults

(valid for the permanent exhibitions)

|

2800 HUF

|

/ capita

|

|

Ticket for adults

|

3200 HUF

|

|

|

Group ticket for adults

|

2900 HUF

|

|

|

Ticket for students

(valid for the permanent exhibitions)

|

1400 HUF

|

/ capita

|

|

Ticket for students

|

1600 HUF

|

|

|

Group ticket for students

|

1400 HUF

|

|

|

Ticket for pensioners

(valid for the permanent exhibitions)

|

1400 HUF

|

/ capita

|

|

Audio guide

|

800 HUF

|

|

|

Video

|

1000 HUF

|

The Antique Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts set off a chamber exhibition series entitled 'The Work of Art of the Month' four years ago. The main objective was to show accomplishments of work done at the Collection regularly. Among the objects shown there are new acquisitions and restored artworks, some of them scientifically studied .

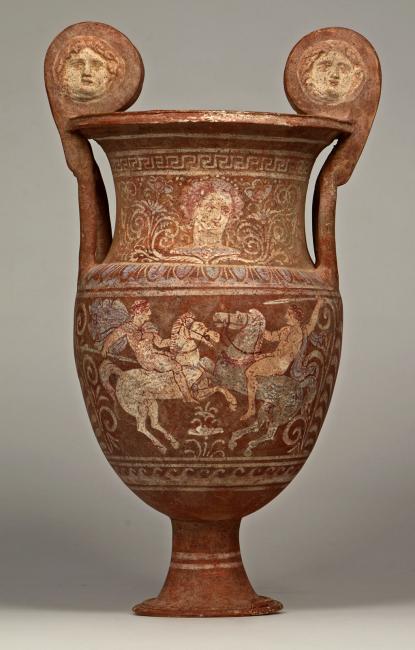

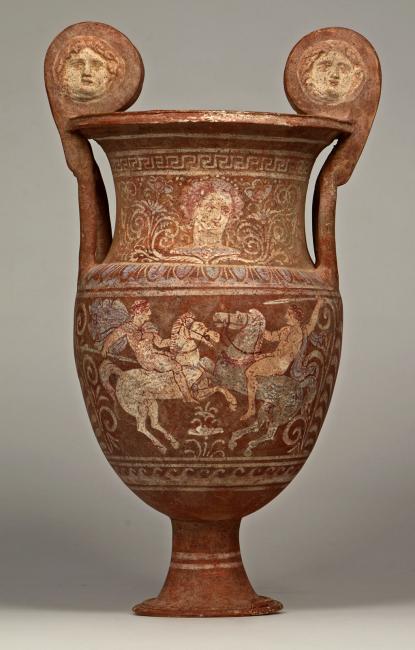

The exhibition in the summer of 2008 shows solely one object, a colored vase.

Both Greek and Roman writers held the idea that only barbarians drank wine without mixing it with something. So it is understandable that the large vessel with big mouth, the 'crater' in which wine was mixed could not be omitted at feasts and the symposiums following them. The more valuable pieces were made of bronze and were often the size of a man. The 'craters' made of clay were usually decorated with figural painting. This variation was related to a certain region.

The type that was called 'voluta crater' originated in Sparta. It was initially horseshoe shaped and ended in a spiral shape beginning on the handle, a form was popular in Athens in the 6-5th century. It was a sought object among the Ethrusk living in Italy and South-Italian people affiliated with the Greek. In the first quarter of the 4th century volute craters disappeared from the market in Athens while in South-Italy it was among one of the most popular forms, especially in workshops of Apulia. The variation in which the volutes gave place to disks with a coloured mask embossment evolved in these workshops. The Antique Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts acquired one of these recently.

Based on decorations typical of Athens, these vases were usually decorated with red-figure technique with dark brown or black background. This decoration first appeared in Athens around 530 and remained in fashion for two centuries. However, from the middle of the 4th century, it went out of fashion and in Athens disappeared completely. In significant workshops in South-Ital, especially in Tarentum, red-figure vases were still made for the next half century. However, need for newer technique and colours developed. The new ornament, motley colour plant ornaments on black background first appeared in Tarentum and became popular in the region. It was the Gnathia technique. Experiments with other decorations were also known of. It seems, the location of workshops where completely new decorations were applied completely opposed to traditional ones was in Canosa and its region, mainly Arpi.

The town with 30.000 citizens now is situated on the left bank of the River Ofatnto, a few kms from the Adriatic Sea; the northern part of Apulia was the antique Canusium. Remains from ceramic workshops verify that the town used to be a flourishing centre of vase-wrights while Greek vessels betraying the need of the natives appeared on market too. The culture of the town could be characterised with continuous interaction of Greek and native citizens. According to a local tradition, Diomedes founded it returning from Troy and Horatius called Canosa a bilingual town even after a three-century reign of the Romans. The habitat became a town in the 4th century AD. The best masters making red-figure vases in Tarentum sold their product well, while the still pouring Greek produce sols well too, in the second part of the century. In the end of the century apprentices of these masters founded workshops with greater production capacity.

The new decorations were first applied in workshops that had formerly favoured the red-figure technique, as well as in workshops related to these. The very unique decoration on the vase now shown in Budapest belongs to the former. The form of the vase does not differ from that of the red-figure ones but the proportion does. However, the decoration is completely the opposite of that of the vases made in Athens: painting on brownish-red surface. It was apparently an experiment of the later popular ‘polychrom’ decoration made in a workshop in Tarentum. Based on the decoration, the vase was most possibly made by followers of the most significant master of Tarentum, the painter Dareios. During the time it was made, around 320-280, voluta-craters disappeared completely from Tarentum and its region. In workshops in Canose-Daunia it was solely used at burials to accompany the deceased shown by the hole at the bottom of the vase, just as the case with the vase shown in Budapest. The interpretation of the decoration should also be considered based on the vase's funeral role.

The main side differs from the back side in that only it was only decorated with relief masks while the back side was without any decoration.The main scene is a symmetrically portrayed face of a horse riding boy. The obvious difference lays in the colour of horses. One is lights colour while the other is bluish-grey, familiar colours as these were used with the portrayal of the God of the Underworld. The scene is thus is 'mortis et vitae iudicium', quoting the title of a lost Roman drama, fight to death. The interpretation according to which the two fighters are the same figures in different situation may not be so unrealistic. The outcome of the fight is signed by the function of the vase. But to interpret the vase, we must not forget about the female figure rising from the flowers at the neck. In this form, it often accompanied vases portraying grave chambers. According to an excellent interpreter of grave vases, it is a 'symbolic reflection on flowering survival in a world opposed to death.' We can only guess if the female head on the back can be integrated into this interpretation.

The scene is unique on known vases from South-Italy but not without antecedent. The ceramic from the tradition preserving town of Apula from two centuries before, with little Greek influence both on the main side and back repeats the scene found on the 'crater' shown in Budapest: men riding red and black horses.The other side, however, shows a more desolate end: the rider on the red horse appears headless while the man on the black horse is replaced by a vulture. What role the new Orphic-Dyonisos religion widespread between the time of making of the vases played in the portrayal of the two scenes can only be guessed.

János György Szilágyi

The exhibition in the summer of 2008 shows solely one object, a colored vase.

Both Greek and Roman writers held the idea that only barbarians drank wine without mixing it with something. So it is understandable that the large vessel with big mouth, the 'crater' in which wine was mixed could not be omitted at feasts and the symposiums following them. The more valuable pieces were made of bronze and were often the size of a man. The 'craters' made of clay were usually decorated with figural painting. This variation was related to a certain region.

The type that was called 'voluta crater' originated in Sparta. It was initially horseshoe shaped and ended in a spiral shape beginning on the handle, a form was popular in Athens in the 6-5th century. It was a sought object among the Ethrusk living in Italy and South-Italian people affiliated with the Greek. In the first quarter of the 4th century volute craters disappeared from the market in Athens while in South-Italy it was among one of the most popular forms, especially in workshops of Apulia. The variation in which the volutes gave place to disks with a coloured mask embossment evolved in these workshops. The Antique Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts acquired one of these recently.

Based on decorations typical of Athens, these vases were usually decorated with red-figure technique with dark brown or black background. This decoration first appeared in Athens around 530 and remained in fashion for two centuries. However, from the middle of the 4th century, it went out of fashion and in Athens disappeared completely. In significant workshops in South-Ital, especially in Tarentum, red-figure vases were still made for the next half century. However, need for newer technique and colours developed. The new ornament, motley colour plant ornaments on black background first appeared in Tarentum and became popular in the region. It was the Gnathia technique. Experiments with other decorations were also known of. It seems, the location of workshops where completely new decorations were applied completely opposed to traditional ones was in Canosa and its region, mainly Arpi.

The town with 30.000 citizens now is situated on the left bank of the River Ofatnto, a few kms from the Adriatic Sea; the northern part of Apulia was the antique Canusium. Remains from ceramic workshops verify that the town used to be a flourishing centre of vase-wrights while Greek vessels betraying the need of the natives appeared on market too. The culture of the town could be characterised with continuous interaction of Greek and native citizens. According to a local tradition, Diomedes founded it returning from Troy and Horatius called Canosa a bilingual town even after a three-century reign of the Romans. The habitat became a town in the 4th century AD. The best masters making red-figure vases in Tarentum sold their product well, while the still pouring Greek produce sols well too, in the second part of the century. In the end of the century apprentices of these masters founded workshops with greater production capacity.

The new decorations were first applied in workshops that had formerly favoured the red-figure technique, as well as in workshops related to these. The very unique decoration on the vase now shown in Budapest belongs to the former. The form of the vase does not differ from that of the red-figure ones but the proportion does. However, the decoration is completely the opposite of that of the vases made in Athens: painting on brownish-red surface. It was apparently an experiment of the later popular ‘polychrom’ decoration made in a workshop in Tarentum. Based on the decoration, the vase was most possibly made by followers of the most significant master of Tarentum, the painter Dareios. During the time it was made, around 320-280, voluta-craters disappeared completely from Tarentum and its region. In workshops in Canose-Daunia it was solely used at burials to accompany the deceased shown by the hole at the bottom of the vase, just as the case with the vase shown in Budapest. The interpretation of the decoration should also be considered based on the vase's funeral role.

The main side differs from the back side in that only it was only decorated with relief masks while the back side was without any decoration.The main scene is a symmetrically portrayed face of a horse riding boy. The obvious difference lays in the colour of horses. One is lights colour while the other is bluish-grey, familiar colours as these were used with the portrayal of the God of the Underworld. The scene is thus is 'mortis et vitae iudicium', quoting the title of a lost Roman drama, fight to death. The interpretation according to which the two fighters are the same figures in different situation may not be so unrealistic. The outcome of the fight is signed by the function of the vase. But to interpret the vase, we must not forget about the female figure rising from the flowers at the neck. In this form, it often accompanied vases portraying grave chambers. According to an excellent interpreter of grave vases, it is a 'symbolic reflection on flowering survival in a world opposed to death.' We can only guess if the female head on the back can be integrated into this interpretation.

The scene is unique on known vases from South-Italy but not without antecedent. The ceramic from the tradition preserving town of Apula from two centuries before, with little Greek influence both on the main side and back repeats the scene found on the 'crater' shown in Budapest: men riding red and black horses.The other side, however, shows a more desolate end: the rider on the red horse appears headless while the man on the black horse is replaced by a vulture. What role the new Orphic-Dyonisos religion widespread between the time of making of the vases played in the portrayal of the two scenes can only be guessed.

János György Szilágyi