2024. July 27. Saturday

Kunsthalle - Budapest

|

Address: 1146, Budapest Dózsa György út 37.

Phone number: (1) 460-7000, (1) 363-2671

E-mail: info@mucsarnok.hu

Opening hours: Tue-Wed 10-18, Thu 12-20, Fri-Sun 10-18

|

The exhibition has closed for visitors.

Ticket prices

|

Program ticket

|

2500 HUF

|

Art historians tend to associate Lívius Gyulai with the so-called great generation of Hungarian graphic artists, where he was the ‘youngest son’ among the doyens – Kondor, Würtz, Hincz, Reich, Rékassy – and, just like in folk tales, he was the one who was constantly reborn.

Grand masters are not measured in feet or inches, nor by the number of their sketches. Gyulai may not have even known what a sketch was. He missed it out and drew the immaculate final version. A rubber? He probably never needed one. He moved between styles with obvious naturalness, donning Villon’s cloak, Lúdas Matyi’s boots and Leacock’s top hat as if they had been tailor-made for him from the beginning. Yet not only did he know how to be ‘authentic’, but also, perhaps even more than this, he knew how to put all the rules in quotation marks, while wearing a mischievous smile on his face. Just like other writers and poets in their own field he was a master at bending and changing form. He had everything at his fingertips - fine dottings, dynamic lines and casual brushstrokes. His art is full of exciting, brilliantly executed shifts of perspective and the corresponding changes of style. The horizon of the characters, the draughtsman’s perspective and the viewer’s field of vision are interchangeable: ‘Dear Reader, please continue, you could have drawn this line yourself; or you, Sir, you could have placed this stain here, if you wanted to; or perhaps, you, little miss, you could have put it over there’. We can almost feel the warmth of his handshake. And the loupe wired to our nose is fogging up. The reader, who ‘completes’ the work is a companion, a friend, a pal, and a mate here to equal degree.

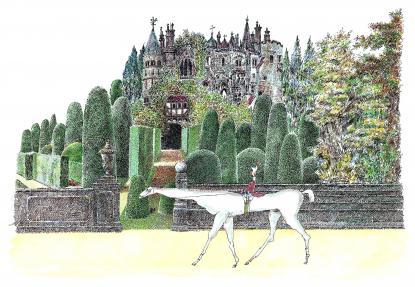

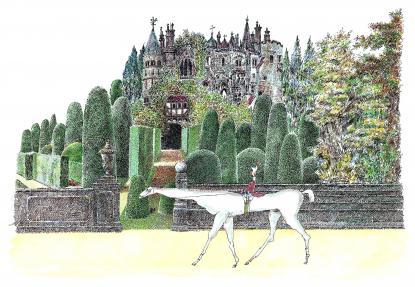

The naturalness of Gyulai’s book illustrations is captivating. On the drawing board propped on his knee one can perceive a rolled-out horizon. Weöres’s Psyché, Sterne’s Sentimental Journeys, Molière’s The Miser, Leacock’s Gertrude, Balzac’s Droll Stories, Csokonai’s Karnyóné, the sweet-sweet Krúdyades, Hadova és Hamuka, Captain De Ronch, the emblematic cartoon alter ego Jonah, and of course his little brother, the diarist Bad Boy – which are seemingly very different subjects, yet for each of them he finds the perfect form, impeccable technique and ideal style, and in each case it is unquestionably he who stands behind them. Illustrations are like literary translations, but instead of another language, they recreate a work of art in another genre, in fine art. A good illustrator is an independent personality with his own vision of the literary work, rather than someone carrying out the translation task with slavish precision. Are good illustrations necessarily a forgery, and in a similar vein to this, is it inevitable that good translations will have a degree of distortion in them? It is certainly a strange paradox worth further reflection. If one reads the works he illustrated – even if one has read most of them previously – one will notice that it is Gyulai’s cleverly reciting, husky voice that speaks, it is his accents that interpret the stories for us. He has after all been the illuminator of Hungarian literature and the interpreter of world literature for many generations. I don’t think I’m being overboard in listing Miguel de Cervantes’ Gyulai, Líviusz de Balzac, Mihály Gyulai Vitéz and Líviusz Lázár as my favourite authors.

Wood engravings? Copper etchings? Lithographic prints? Lino-cuts? Gyulai did not have to choose, he was rather chosen by the poetess Psyché – because, of course, she knew that she could respect the greatest titologist of all in his person (meaning that no one in the history of the arts, or at least not since Willendorf, has ever created such sensual tits as he has) – and by Baron Münchhausen, Lipitlotty, the cavalier of Pest, the lady with the diabolo, and the other one with the open bosom once grazing a dragon (a flirtation with Cyrano here, a liaison with Szindbád there), then moving into old Casanova’s cart or riding the passionate rhinoceros of Albrecht Dürer with bare buttocks. An art-historical highlight: the very first rhinoceros (back in Jókai’s time still called a horn-nose), the Asian pearl of bestiaries decorated with a narwal-fang (stuffed with horsehair) straight from Lisbon stomping at the Oktogon. And fed in Pestújhely. Dürer never actually saw the exotic animal, he was only told about it. His pen sketch of the rhinoceros he had imagined based on the news, and the famous wood engraving made after the sketch are this creature’s first artistic representations, and since then la nave va..., as in Fellini’s film. Gyulai’s version is one of the most recent depictions, at least until now. As far as I know, he has engraved the rhinoceros at least three times. I suppose I do not need to explain the symbolism or the self-irony lurking behind the choice of this emblematic beast. The drawing of an animal never seen, only imagined, is a symbolic stand-up for reflective as opposed to representational art. The rhinoceros – from Dürer to Gyulai – proves that imagination is capable of creating new creatures and unknown worlds. Yes, this clumsy, coarse, half-extinct creature represents the freehand artist working with wood engravings, lithographs, pen drawings and copper etchings – the illustrator himself.

Líviusz Gyulai was already a regularly exhibiting, noted graphic artist and even a nationally known illustrator when he joined Pannónia Film Studio in 1974. This studio was the ‘official’ institution of Hungarian animation at that time. He soon embarked on his first independent film, Delfinia (1976, co-directed by Elek Lisziák and with music composed by Levente Szörényi). He was wandering around Gyula Krúdy’s Óbuda when he started Delfinia, which, therefore, is imbued with krúdyesque nostalgia.

The second film in his cinematic oeuvre, Új lakók [New Dwellers] (1977) became a real hit. He chose his subject from the environment of his studio apartment on November 7 Square [now: Oktogon], or perhaps it was the subject that chose him. The protagonists of Új lakók are a family of centaurs who, with their strange lifestyle, weird friends (mermaids, fauns, minotaurs and harpies come to visit them) and of course their mythological nudity are very different from the petty bourgeois environment of the grey apartment block with its open corridors. The residents, led by the shrewish female caretaker make their lives a living hell. Unable – and reluctant – to fit in, the gentle centaurs leave the house, which, it turns out, will never be the same as it was before. The remaining inhabitants, especially the children, begin to realise that there might and should be other ways to live their lives.

Film history (or at least the National Film Institute’s jury) has chosen Jónás [Jonah] (1996) as the ‘standard work’ from his rich oeuvre. The graphics referring to the story – or, more precisely, to the cinematographic paraphrase of the story – of the most human prophet from the Old Testament were already completed around 1956, but the film itself was not made until later. Its ‘minimalism’ (two characters, one location), an outlier in the oeuvre, was also made special by the underlying political touch.

In the 6-minute Szindbád, bon voyage! (1998), a ragged, homeless man searching through rubbish takes to the road on a magic flying carpet found among the same rubbish and becomes the protagonist of a frenetic dream journey interweaving space and time.

Az én kis városom [My Small Town] (2001) is also a biographical film. It is a nostalgic postcard, a reminiscence of childhood passed: tiny pieces of puzzle, shops, buildings, people, dreams, fables, love stories, all set in the city of ‘Gyulai’s own Amarcord’: Sopron.

His 7-minute animation Könny nem marad szárazon… [Tears Won’t Stay Dry…] (2003) was inspired by Stephen Leacock, just like one of his most richly engraved linoleum blocks, Gertrúd a nevelőnő [Gertrude, the Governess] from 1971, a print of which can be found in the collection of the Uffizi Gallery.

In most of his films, Líviusz Gyulai is spinning yarns, being witty, coming up with and dropping ideas, weaving the thread of the tale as capriciously and casually as if he were chatting to his friends. Those who had the opportunity to listen to him over a glass of wine (tinto rosso - Tintoretto) will know that even the most far-fetched stories, while all sorts of things happen in them, return to their main subject – which is perhaps no longer important – with their own double Möbius twist, because the flavours and absurdities, the sights and the topics, i.e. the style and humour override everything anyway. It was perhaps only Fellini who could play around with such similar abandon.

Gyulai’s film scripts are also works of art in their own right, illustrated albums on the basis of which not only he, but almost anyone could direct the film. In fact, this is what is happening now, new episodes to the series Egy jenki Arthur király udvarában [A Yankee in King Arthur’s Court], representing his last - posthumous - films, are being shot by the crew that has worked with him for decades, under the direction of Emmy Vennes, a partner in life as well as in creation, and ‘co-director’ Csaba Máli.

Grand masters are not measured in feet or inches, nor by the number of their sketches. Gyulai may not have even known what a sketch was. He missed it out and drew the immaculate final version. A rubber? He probably never needed one. He moved between styles with obvious naturalness, donning Villon’s cloak, Lúdas Matyi’s boots and Leacock’s top hat as if they had been tailor-made for him from the beginning. Yet not only did he know how to be ‘authentic’, but also, perhaps even more than this, he knew how to put all the rules in quotation marks, while wearing a mischievous smile on his face. Just like other writers and poets in their own field he was a master at bending and changing form. He had everything at his fingertips - fine dottings, dynamic lines and casual brushstrokes. His art is full of exciting, brilliantly executed shifts of perspective and the corresponding changes of style. The horizon of the characters, the draughtsman’s perspective and the viewer’s field of vision are interchangeable: ‘Dear Reader, please continue, you could have drawn this line yourself; or you, Sir, you could have placed this stain here, if you wanted to; or perhaps, you, little miss, you could have put it over there’. We can almost feel the warmth of his handshake. And the loupe wired to our nose is fogging up. The reader, who ‘completes’ the work is a companion, a friend, a pal, and a mate here to equal degree.

The naturalness of Gyulai’s book illustrations is captivating. On the drawing board propped on his knee one can perceive a rolled-out horizon. Weöres’s Psyché, Sterne’s Sentimental Journeys, Molière’s The Miser, Leacock’s Gertrude, Balzac’s Droll Stories, Csokonai’s Karnyóné, the sweet-sweet Krúdyades, Hadova és Hamuka, Captain De Ronch, the emblematic cartoon alter ego Jonah, and of course his little brother, the diarist Bad Boy – which are seemingly very different subjects, yet for each of them he finds the perfect form, impeccable technique and ideal style, and in each case it is unquestionably he who stands behind them. Illustrations are like literary translations, but instead of another language, they recreate a work of art in another genre, in fine art. A good illustrator is an independent personality with his own vision of the literary work, rather than someone carrying out the translation task with slavish precision. Are good illustrations necessarily a forgery, and in a similar vein to this, is it inevitable that good translations will have a degree of distortion in them? It is certainly a strange paradox worth further reflection. If one reads the works he illustrated – even if one has read most of them previously – one will notice that it is Gyulai’s cleverly reciting, husky voice that speaks, it is his accents that interpret the stories for us. He has after all been the illuminator of Hungarian literature and the interpreter of world literature for many generations. I don’t think I’m being overboard in listing Miguel de Cervantes’ Gyulai, Líviusz de Balzac, Mihály Gyulai Vitéz and Líviusz Lázár as my favourite authors.

Wood engravings? Copper etchings? Lithographic prints? Lino-cuts? Gyulai did not have to choose, he was rather chosen by the poetess Psyché – because, of course, she knew that she could respect the greatest titologist of all in his person (meaning that no one in the history of the arts, or at least not since Willendorf, has ever created such sensual tits as he has) – and by Baron Münchhausen, Lipitlotty, the cavalier of Pest, the lady with the diabolo, and the other one with the open bosom once grazing a dragon (a flirtation with Cyrano here, a liaison with Szindbád there), then moving into old Casanova’s cart or riding the passionate rhinoceros of Albrecht Dürer with bare buttocks. An art-historical highlight: the very first rhinoceros (back in Jókai’s time still called a horn-nose), the Asian pearl of bestiaries decorated with a narwal-fang (stuffed with horsehair) straight from Lisbon stomping at the Oktogon. And fed in Pestújhely. Dürer never actually saw the exotic animal, he was only told about it. His pen sketch of the rhinoceros he had imagined based on the news, and the famous wood engraving made after the sketch are this creature’s first artistic representations, and since then la nave va..., as in Fellini’s film. Gyulai’s version is one of the most recent depictions, at least until now. As far as I know, he has engraved the rhinoceros at least three times. I suppose I do not need to explain the symbolism or the self-irony lurking behind the choice of this emblematic beast. The drawing of an animal never seen, only imagined, is a symbolic stand-up for reflective as opposed to representational art. The rhinoceros – from Dürer to Gyulai – proves that imagination is capable of creating new creatures and unknown worlds. Yes, this clumsy, coarse, half-extinct creature represents the freehand artist working with wood engravings, lithographs, pen drawings and copper etchings – the illustrator himself.

Líviusz Gyulai was already a regularly exhibiting, noted graphic artist and even a nationally known illustrator when he joined Pannónia Film Studio in 1974. This studio was the ‘official’ institution of Hungarian animation at that time. He soon embarked on his first independent film, Delfinia (1976, co-directed by Elek Lisziák and with music composed by Levente Szörényi). He was wandering around Gyula Krúdy’s Óbuda when he started Delfinia, which, therefore, is imbued with krúdyesque nostalgia.

The second film in his cinematic oeuvre, Új lakók [New Dwellers] (1977) became a real hit. He chose his subject from the environment of his studio apartment on November 7 Square [now: Oktogon], or perhaps it was the subject that chose him. The protagonists of Új lakók are a family of centaurs who, with their strange lifestyle, weird friends (mermaids, fauns, minotaurs and harpies come to visit them) and of course their mythological nudity are very different from the petty bourgeois environment of the grey apartment block with its open corridors. The residents, led by the shrewish female caretaker make their lives a living hell. Unable – and reluctant – to fit in, the gentle centaurs leave the house, which, it turns out, will never be the same as it was before. The remaining inhabitants, especially the children, begin to realise that there might and should be other ways to live their lives.

Film history (or at least the National Film Institute’s jury) has chosen Jónás [Jonah] (1996) as the ‘standard work’ from his rich oeuvre. The graphics referring to the story – or, more precisely, to the cinematographic paraphrase of the story – of the most human prophet from the Old Testament were already completed around 1956, but the film itself was not made until later. Its ‘minimalism’ (two characters, one location), an outlier in the oeuvre, was also made special by the underlying political touch.

In the 6-minute Szindbád, bon voyage! (1998), a ragged, homeless man searching through rubbish takes to the road on a magic flying carpet found among the same rubbish and becomes the protagonist of a frenetic dream journey interweaving space and time.

Az én kis városom [My Small Town] (2001) is also a biographical film. It is a nostalgic postcard, a reminiscence of childhood passed: tiny pieces of puzzle, shops, buildings, people, dreams, fables, love stories, all set in the city of ‘Gyulai’s own Amarcord’: Sopron.

His 7-minute animation Könny nem marad szárazon… [Tears Won’t Stay Dry…] (2003) was inspired by Stephen Leacock, just like one of his most richly engraved linoleum blocks, Gertrúd a nevelőnő [Gertrude, the Governess] from 1971, a print of which can be found in the collection of the Uffizi Gallery.

In most of his films, Líviusz Gyulai is spinning yarns, being witty, coming up with and dropping ideas, weaving the thread of the tale as capriciously and casually as if he were chatting to his friends. Those who had the opportunity to listen to him over a glass of wine (tinto rosso - Tintoretto) will know that even the most far-fetched stories, while all sorts of things happen in them, return to their main subject – which is perhaps no longer important – with their own double Möbius twist, because the flavours and absurdities, the sights and the topics, i.e. the style and humour override everything anyway. It was perhaps only Fellini who could play around with such similar abandon.

Gyulai’s film scripts are also works of art in their own right, illustrated albums on the basis of which not only he, but almost anyone could direct the film. In fact, this is what is happening now, new episodes to the series Egy jenki Arthur király udvarában [A Yankee in King Arthur’s Court], representing his last - posthumous - films, are being shot by the crew that has worked with him for decades, under the direction of Emmy Vennes, a partner in life as well as in creation, and ‘co-director’ Csaba Máli.