2025. December 28. Sunday

Hungarian Jewish Museum and Archives - Budapest

|

|

Address: 1075, Budapest Dohány utca 2.

Phone number: (1) 343-6756

E-mail: info@zsidomuzeum.hu

Opening hours: 01.11-28.02.: Sun-Thu 10-16, Fri 10-14

01.03-31.10.:Sun-Thu 10-18, Fri 10-16.30 |

The exhibition has closed for visitors.

2009.03.17. - 2009.07.12.

Museum tickets, service costs:

|

Ticket for adults

|

2000 HUF

|

|

|

Ticket for students

|

850 HUF

|

|

|

Ticket for pensioners

|

850 HUF

|

|

|

Guide

|

2400 HUF

|

/ capita

|

|

Photography

|

500 HUF

|

A few terms at the medical faculty of the university- following his graduation in the grammar school- this is what can be regarded as his educational level.

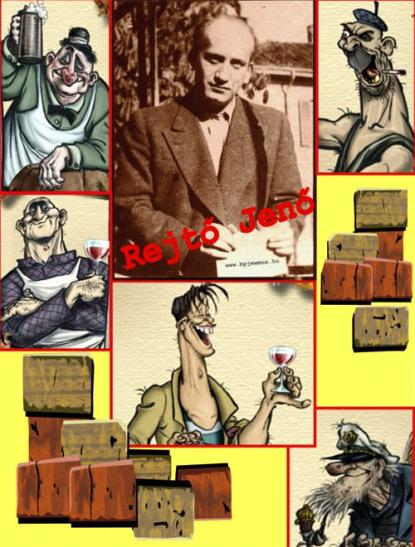

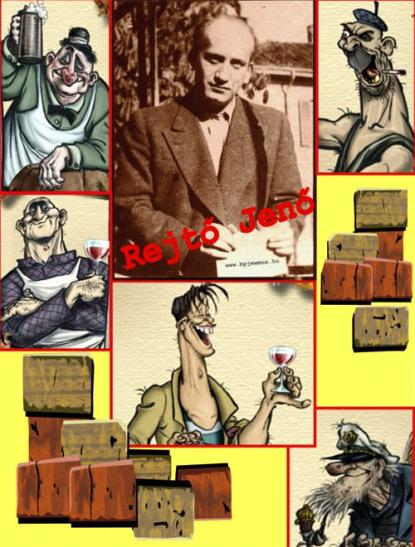

His profession both according to his passport and in his military documents was indicated as: WRITER.

He did not start his career as the author of cabaret scenes or amusing trashy novels and that is why he never completely became that. We can read among his first literary attempts affecting poems or a travel diary documenting his European trappings. All along his life thenafter he was "pouring" by dozens cabaret-jokes, single-act scenes, operettas and other light form literary moving band products for everyday use.

His principal artistic form however has become the trashy novel more precisely the parody of a trashy novel: he wrote his books mostly under pen-names, or he at times "translated" them. The cheap penny dreadfuls, inexpensive novels running under the name P. HOWARD could be sold better under this English- sounding name reminding the general reader of the authors of the legionary novels fashionable in this period.

His person was surrounded by legends, the contemporaries and the grateful succeeding generations did not make every effort to document his career with accurate facts. We have just a few authentic facts on his life- and what we know on his death coming about at the age of 38 years that is in its cruelty too, uncertain.

Opposed to these the world of his works is certainty itself. The person who has never been in North-Africa, not even in Csepel (XXI. District of Budapest) yet, knows from the novel Az elveszett cirkáló (The lost Cruiser) what a harbor looks like; he who did not see sand in Morocco or Tunisia, but hadn't even been to the country-side from the coffee-houses of the Király street (VII. District of Budapest), he would know from the novel A láthatatlan légió (The invisible legion) how a desert looks like. During an excursion on the Danube however the steamer starts to look like the schooner Brigitta or Nekivág and in the taverns of Pest one could feel himself in Pireus.

Jenő Rejtő, unlike the trashy novel writers, did not try to make an unreal world to look true; however his phraseology of particular structure shaping even the everyday language has turned the fictive scenes and figures of his novels into existing reality.

The man in the street and the man of hyper intellect can to the present day equally feel both the strange creator of Hungarian literature in Pest and of European Jewish humor and his unrepeatable works to be his own.

Verbality and visuality cannot be separated in his wordings. Therefore is it difficult to speak about Rejtő and therefore it is difficult to put his novels on the screen. As if being between the two- moreover kept in evidence as an inferior form art- the picture-novel would be able to visualize simultaneously the effect of word and picture reinforcing one another.

The exhibition does not merely rely upon the very the very few material remains from the life of Jenő Rejtő, upon the manuscripts, publications of the author. The fictive relics and false documents of Rejtő's world are equally important, as these prove the self-lawfulness of texts surviving the author and making him survive, he could have also made up this exhibition- parody about his own life.

Official documents have dated the death of Jenő Rejtő forced-labourer to New Year's day of 1943. He was seen beside the village Jevdakovo in the vicinity of Voronyezh, for the last time. He hasn't got any grave- was he frozen, shot, fell into captivity again, maybe escaped?

His novels are always with a happy end. The playful yet vigorous or just stumbling heroes of P. Howard do always overcome destiny. They play with death, yet they survive. Jenő Rejtő could not be a hero and did not want to die, however the prisoners of the Csontbrigád (Bone-brigade) sentenced to forced-labor had no chance in the Russian snow- fields: Jenő Reich (Rejtő) never returned from the "Légió" (Legion) of the curve of the river Don.

To go or to die? There is no choice between the two. The cruiser was stolen by "Fred Piszkos", the courier by "Prücsök" the possibility of a decision was stolen by history. "What could a man do, whose tragedy was stolen?" (Jenő Rejtő)

He did not start his career as the author of cabaret scenes or amusing trashy novels and that is why he never completely became that. We can read among his first literary attempts affecting poems or a travel diary documenting his European trappings. All along his life thenafter he was "pouring" by dozens cabaret-jokes, single-act scenes, operettas and other light form literary moving band products for everyday use.

His principal artistic form however has become the trashy novel more precisely the parody of a trashy novel: he wrote his books mostly under pen-names, or he at times "translated" them. The cheap penny dreadfuls, inexpensive novels running under the name P. HOWARD could be sold better under this English- sounding name reminding the general reader of the authors of the legionary novels fashionable in this period.

His person was surrounded by legends, the contemporaries and the grateful succeeding generations did not make every effort to document his career with accurate facts. We have just a few authentic facts on his life- and what we know on his death coming about at the age of 38 years that is in its cruelty too, uncertain.

Opposed to these the world of his works is certainty itself. The person who has never been in North-Africa, not even in Csepel (XXI. District of Budapest) yet, knows from the novel Az elveszett cirkáló (The lost Cruiser) what a harbor looks like; he who did not see sand in Morocco or Tunisia, but hadn't even been to the country-side from the coffee-houses of the Király street (VII. District of Budapest), he would know from the novel A láthatatlan légió (The invisible legion) how a desert looks like. During an excursion on the Danube however the steamer starts to look like the schooner Brigitta or Nekivág and in the taverns of Pest one could feel himself in Pireus.

Jenő Rejtő, unlike the trashy novel writers, did not try to make an unreal world to look true; however his phraseology of particular structure shaping even the everyday language has turned the fictive scenes and figures of his novels into existing reality.

The man in the street and the man of hyper intellect can to the present day equally feel both the strange creator of Hungarian literature in Pest and of European Jewish humor and his unrepeatable works to be his own.

Verbality and visuality cannot be separated in his wordings. Therefore is it difficult to speak about Rejtő and therefore it is difficult to put his novels on the screen. As if being between the two- moreover kept in evidence as an inferior form art- the picture-novel would be able to visualize simultaneously the effect of word and picture reinforcing one another.

The exhibition does not merely rely upon the very the very few material remains from the life of Jenő Rejtő, upon the manuscripts, publications of the author. The fictive relics and false documents of Rejtő's world are equally important, as these prove the self-lawfulness of texts surviving the author and making him survive, he could have also made up this exhibition- parody about his own life.

Official documents have dated the death of Jenő Rejtő forced-labourer to New Year's day of 1943. He was seen beside the village Jevdakovo in the vicinity of Voronyezh, for the last time. He hasn't got any grave- was he frozen, shot, fell into captivity again, maybe escaped?

His novels are always with a happy end. The playful yet vigorous or just stumbling heroes of P. Howard do always overcome destiny. They play with death, yet they survive. Jenő Rejtő could not be a hero and did not want to die, however the prisoners of the Csontbrigád (Bone-brigade) sentenced to forced-labor had no chance in the Russian snow- fields: Jenő Reich (Rejtő) never returned from the "Légió" (Legion) of the curve of the river Don.

To go or to die? There is no choice between the two. The cruiser was stolen by "Fred Piszkos", the courier by "Prücsök" the possibility of a decision was stolen by history. "What could a man do, whose tragedy was stolen?" (Jenő Rejtő)